The answer is: No. Sorry, guys.

More seriously, there are a few distinct questions embedded in this one. The first is quasi-ontological. Is there really any such thing as Marxist economics? Now, I am not one to rule out the existence of a phenomenon on the basis of definitions and syllogisms, and I won't do that in this case either. There are people who call themselves Marxists who were trained in and/or teach in economics departments, or who otherwise publish work which they refer to as "economics" or, in a conscious turn of an old phrase, "political economy". In that sense, there are Marxist economists, and the work they publish can be called, if they insist, "Marxist economics" or "Marxian political economy".

But the fact remains that Marx did not refer to his own work as "political economy," but as the "critique of political economy." By which he meant the historicization of the fundamental conceptions of political economy, in order to demonstrate the limits of their ability to describe capital's existence, coming-to-be and hypothesized passing away. Such a step was necessary to move from the realm of ideology--the eternalization of bourgeois relations of production--into science. The purpose of this argument is not to ultimatistically insist that any Marxist interested in the domain of economic relationships refer to her or his work as forming part of the corpus of the "critique of political economy"--the phrase is a mouthful, and the mere avowal of its importance does not make the underlying work true and accurate any more than extensive citations of Marx can make a work Marxist. But it is to say that unless such work operates with the methods and spirit of critique--that is, the examination of economic phenomena in their genesis, immanent contradictions, antagonistic relations and ultimate perishability--then it is neither Marxist nor scientific.

The question then becomes whether there is any such work taking place, whether under the heading of "Marxist economics," "Marxian political economy," or (as Sy Landy would joke to express a justifiable impatience with debates over nomenclature) "Herbie": And to that I would give, based on a sampling of the work I saw presented at the Historical Materialism conference, a provisional "Yes."

There remains another question, however, namely whether the work currently being carried on in the spirit of the critique of political economy is being carried out as a collective effort, in which new investigations either build upon or explicitly and evidentially contradict prior ones and, while there is extensive debate over various questions of interpretation, there are shared methodological approaches to the identification, extraction and analysis of key data. And here, based on the same sampling, as well as recent readings and attendance at other recent events, lead me to the conclusion--still provisional, but with a bit more probability--"No. It has not for some time, and not yet."

On this basis, I would be tempted to hypothesize that the critique of political economy has not been carried on as a collective, non-ideological, theoretical and fact-seeking endeavor for quite some time. The tipping point may well be pinpointable, to the arrest by the Stalinists of I. I. Rubin, though that's an even more tentative hypothesis.

Nonetheless, when I go to left events that are focused on theoretical questions, I tend to focus on the sessions labeled as having to do with "Marxist economics," because I find the topics treated interesting, and I have hope that the presenters and participants are animated by a scientific, truth-seeking spirit. That I am often disappointed in the latter hope gets weighed against the times when I am surprised by its fulfillment.

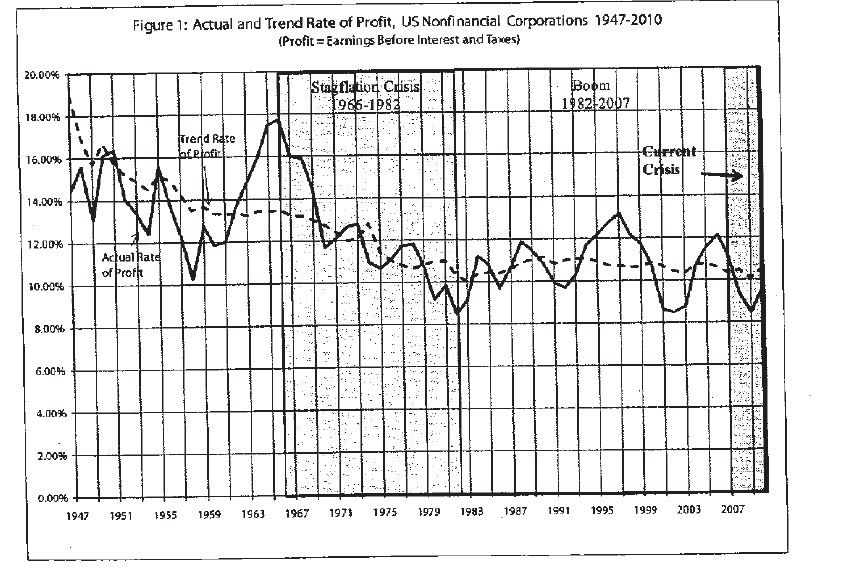

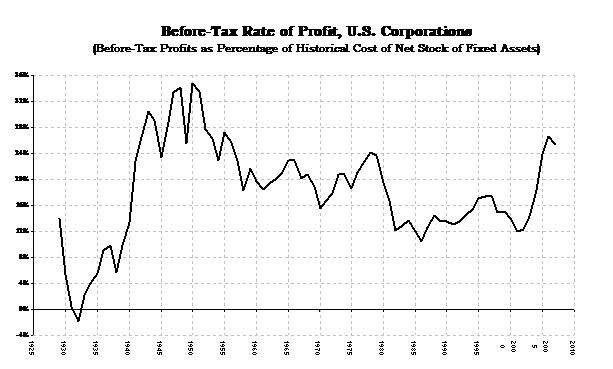

As an example of the phenomena that lead to disappointment, I will point to the seemingly endless debates on how to calculate the historical rate of profit in U.S. capitalism. A number of scholars have made recent attempts to calculate it. They differ sharply on the statistics to use in the calculations and the way to analyze those statistics, and the results are a variety of different historical curves. For the moment I will bracket the question of who's right and who's wrong in the various methodological debates, and just present a few of the resulting figures:

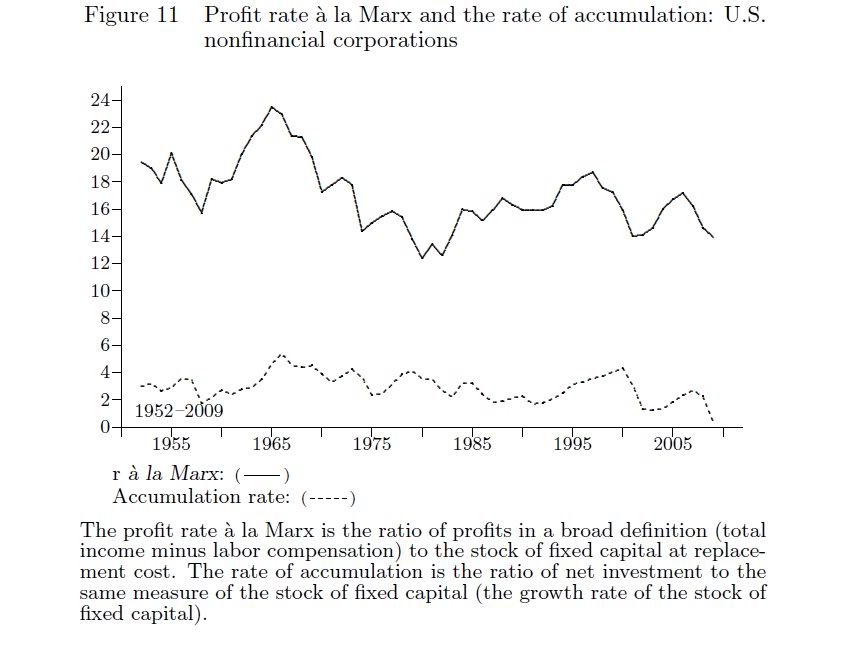

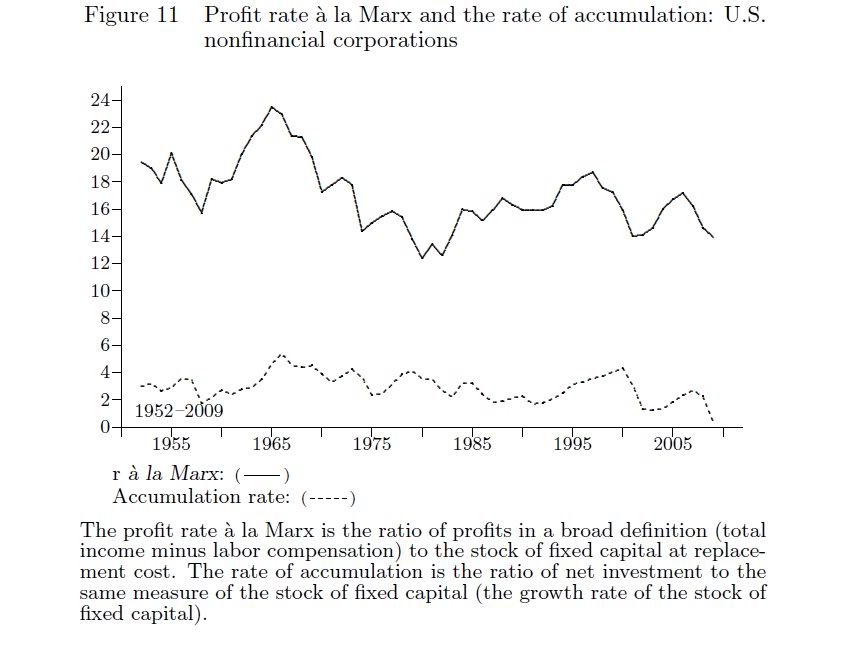

That comes from "The Crisis of the Early 21st Century: A Critical Review of Alternative Interpretations - Preliminary draft," by Gerard Duménil (who spoke at the conference to present on the questions covered in that paper, and whose talk I attended) and Dominique Lévy.

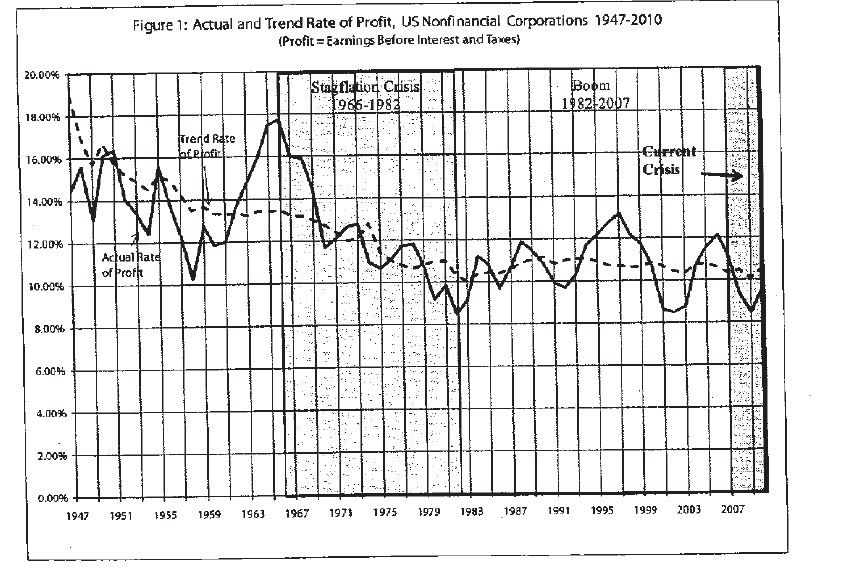

That one is from Anwar Shaikh, The First Great Depression of the 21st Century, who was not at this conference, but apparently had had a bit of a debate with Duménil in the same venue the previous year.

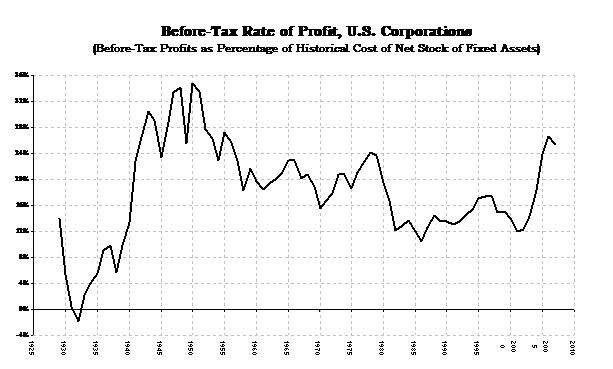

That comes from “The Destruction of Capital” and the Current Economic Crisis by Andrew Kliman--he did give a talk at the conference, though in a different session than Duménil, which I did not attend. I heard from some who did that his presentation was very similar to the one he gave at last November's conference on Economic Crisis and Left Responses.

I would have liked to have also included a chart by Fred Moseley, but encountered a few technical problems. Follow that link, and you'll find a good number of papers and presentations.

The point of this display is to indicate that while there may be some common trends indicated by all the graphs, there are significant enough variances between them to show significant differences of either underlying statistics, methodology or both. And yet they purport to be describing the same thing. Examination of the papers of these various authors will show that this is indeed the case, with debate over such matters as whether or not to subtract any taxes from the nominator (mass of profits), and if so which ones.

Nor can the questions simply be settled with an appeal to the text of Capital, to find out, "what did Marx think?" That's a necessary task if what you are doing is taking Marx's definition of the rate of profit, and analyzing historical data to see if bears out certain key predictions of Marx's, like the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. And that at least is one of the tasks that most of these authors purport to be taking on. But it is not the sole scientific task at stake. There remains the question of whether Marx's definition of the rate of profit was correct, not least because he gave several distinct formalizations of his definition depending upon the context (e.g., one at a single-enterprise level within a single cycle of production, another at an industry-wide scale in a process of simple reproduction, then it gets more complicated when we start talking about accumulation, etc.) And let us not forget that anything from Volumes 2 or 3 was unfinished business at the time of his death, and had to be worked over by Engels to make it at all suitable for publication. Such formalizations are insightful, necessary, an excellent starting point for the examination of the realization of surplus value in the circulation process, the distribution of surplus value among the propertied classes, etc., but only that: A starting point.

But this gets to the question of the purpose served by Marxist academics (and I include in this latter phrase anyone who, by virtue of their social position, even if they do not have a formal affiliation with an academic institution, has the training and leisure to devote a preponderance of their waking hours to research). If one takes as a starting point the view that the proletariat, by virtue of its position within the class struggle, is uniquely positioned to see through the fetishistic relations of capital to understand the real social relations beneath, then a scientific understanding of social phenomena is impossible without a proletarian movement. Without a proletarian movement, there can be no Marxist science, no critique of political economy. But by virtue again of their exploitation by capitalists, atomized proletarians, without the assistance of an organization, cannot create the time or replicate the training needed to crunch the numbers to quantify, visualize and test theories against their underlying phenomena. (By virtue of my white-collar training, then with a three-volume set of Capital, a high-speed internet connection, some trial and error with public-access datasets, and a copy of Excel, I could probably produce something that looked like one of the above charts. But I'd either have to quit my job or stop sleeping for a while. And it wouldn't look as good as it would if I had access to SPSS.)

The role of the academic, then, if Marxist, is as a technician. That is, not determine the problems or the methods, but conduct the kind of heavy analysis toward the problems that they are well-suited to perform. In so doing, they can also point out possible problems emergent from the data that otherwise might not have been noticed.

There is no such science because there is not yet the type of proletarian movement that could authoritatively give direction to such technicians. It is hardly the academics' fault qua academics (though, to the extent that some of them also attempt to function as political leaders, they do bear their share of responsibility as well). And in the absence of that, the best they can do is stumble, happenstance, into the kinds of interesting problems that a renewed proletarian movement, based on a genuine science of revolution, would be able to investigate, and practically settle.

And so the next installment of this essay (which may or may not be preceded by installments of other essays in the works), will do that, discussing some of the interesting problems whose presentations I happened to stumble across at the conference--and then, time permitting, some of the not-so-interesting blind alleys.